News articles emerged this week reporting that Harvard Board of Overseers member, Kat Taylor, is calling for the University to divest from fossil fuel holdings, with Reuters calling the public rebuke a “rare” move. Taylor also posted an opinion piece in the Harvard Crimson outlining her position. Worth noting, the Board of Overseers does not have any direct influence over Harvard’s endowment.

Taylor happens to be the wife of prolific billionaire environmentalist and political donor Tom Steyer, who has also been active in promoting divestment. We’ll set aside some of the known biases for the time being – though you can read some things HERE, and HERE – and instead focus on how just about everyone in the academia and the economic spheres stand against Steyer and Taylor’s position.

Let’s start in 2013, when Harvard President Drew Faust made a sweeping and robust rejection of divestment on behalf of the university. From her remarks:

“The endowment is a resource, not an instrument to impel social or political change … I also find a troubling inconsistency in the notion that, as an investor, we should boycott a whole class of companies at the same time that, as individuals and as a community, we are extensively relying on those companies’ products and services for so much of what we do every day.

“Given our pervasive dependence on these companies for the energy to heat and light our buildings, to fuel our transportation, and to run our computers and appliances, it is hard for me to reconcile that reliance with a refusal to countenance any relationship with these companies through our investments.”

In a 2015 Q&A with the Harvard Gazette, President Faust again reiterated this stance, noting:

“I don’t think that divestment is an appropriate tool, because I don’t think the endowment should be used for exerting political pressure. It is meant to fund the wide range of activities that the University undertakes. As we said before, 35 percent of our operating budget comes from the endowment. That is why people gave their funds to create the endowment. It should not be used as a weapon to exert pressure on one group or another.

“There are many dangers and it has little effective outcome. What would it mean if we sold our investments? Very little, because there are plenty of other people who will invest in those firms.”

In April 2017, activists seized on comments made by Harvard Management Company’s head of natural resources, Colin Butterfield, when he noted the university was “pausing” investments in some fossil fuels. But despite celebrations by the likes of Bill McKibben and others, a Harvard spokesperson was forced to clarify the university’s position and reiterate its opposition to divestment, stating “It certainly was not a change in Harvard’s stance on divestment from fossil fuels, which was laid out in 2013 and remains the university’s position.”

Harvard is not alone in resisting calls to divest from fossil fuels. In recent years the movement has failed to gain any traction and has suffered several high-profile misses. That is because divestment is not only ineffective, but carries substantial costs for universities to consider.

According to a report by Caltech professor Dr. Bradford Cornell, divestment would cost Harvard, Yale, MIT, Columbia, and NYU collectively more than $195 million for each and every year the portfolios are active in the market. Of that group, Harvard’s loss would be the most pronounced, equaling roughly $107 million per year.

What’s more, the director of Harvard’s own Environmental Economics Program, Robert Stavins, agrees the “divestment movement is fundamentally misguided…We should be focusing on actions that will make a real difference.”

So, while billionaire activists may want to push for the pointless policy of divestment, academics, economists and those responsible for the well-being of Harvard’s endowment all disagree. The facts speak for themselves: divestment carries high costs for students and universities, and has no impact on the environment. No wonder Harvard has been smart enough to say no to this costly, empty gesture.

Johns Hopkins University (JHU) is expected to make a recommendation on divestment by September 5, just as students are arriving back on campus. According to campus divest group Refuel Our Future, the University’s Public Interest Investment Advisory Committee (PIIAC) will be providing a response to their divestment proposal and sending its recommendation to the full board for their ultimate decision.

The on-campus divest group has issued a number of demands to the University: divesting from all direct holdings in the Carbon 200, ceasing investment in those companies in the future, investigating how to move its commingled funds into more sustainable portfolios and to move the divested funds into more “sustainable” and “responsible” industries. While well-intentioned, the proposal tends to lean heavily on claims originating from activist groups like 350.org, which have ended up being debunked in the past.

Claim: 73 percent of Johns Hopkins students came out in favor of divesting from the Carbon 200.

Fact: That may seem like a big number, until you look at the participation rate. The referendum was open to all undergraduates, of which there at about 6,500 at JHU. Yet only 397 actually responded to the vote. So at the end of the day, only about six percent of the student body actually voted one way or the other on divestment.

Claim: “Fossil fuel divestment is an effective method” to impact climate change.

Fact: On the contrary, we know that divestment has no impact on the environment, a fact attested to by numerous high profile scientists and academics. Take the comments from Robert Stavins, director of Harvard’s environmental economics program: “The concerns of the students are understandable but the message from the divestment movement is fundamentally misguided. We should be focusing on actions that will make a real difference.” Ultimately, divestment just means the transfer of stock ownership. It does not have any direct environmental benefit.

Claim: If Johns Hopkins divests, the school “will be effectively stating to the world that fossil fuel use as it is now is detrimental and unsustainable.”

Fact: Not exactly. First of all, as we mentioned, divesting from fossil fuels does nothing to impact the climate or emissions. It is a little hypocritical for a school to say that divestment is what will show the world that the use of fossil fuels is detrimental and unsustainable, while at the same time still using said fossil fuels to power its campus. When Notre Dame was debating divestment, University President Father John Jenkins highlighted this very point when he said:

“We’re sitting in a room that’s heated and lighted, and when we drive to where we go, we use fossil fuels. It seems to me that it would seem to be hypocritical to say, ‘we’re going to divest from the companies we rely on for the energy, what we need to do business.’ So I think what we need is a gradual but more determined effort to make our use of energy sustainable.”

Notre Dame ultimately rejected divestment last year.

Harvard University President Drew Faust also made a similar statement when the school rejected divestment in 2013:

“I also find a troubling inconsistency in the notion that, as an investor, we should boycott a whole class of companies at the same time that, as individuals and as a community, we are extensively relying on those companies’ products and services for so much of what we do every day. Given our pervasive dependence on these companies for the energy to heat and light our buildings, to fuel our transportation, and to run our computers and appliances, it is hard for me to reconcile that reliance with a refusal to countenance any relationship with these companies through our investments.”

Claim: Many schools have successfully divested.

Schools like Syracuse, Georgetown and Stanford are frequently used as prime examples of schools that had successfully divested. Refuel our Future also cited these universities as success stories when they wrote:

“…in conjunction with other similar institutions like Georgetown and Stanford, will exert tremendous social pressure on other elite, private universities to divest as well. Many have called Harvard University a “hedge fund with a university attached to it.” The force of Hopkins divesting alone may not force fossil fuel companies to alter their practices. However, the critical mass of Hopkins divesting in concert with Georgetown, Syracuse, Stanford, the University of California, and other institutions such as Harvard and Princeton certainly will.

Fact: None of these schools has actually divested from the Carbon 200 and several have rejected divestment outright. Syracuse is actually the namesake of the “Syracuse Model” for divesting—the notion of only agreeing to sell direct holdings in fossil fuels. This is an empty gesture, as most schools don’t have much in direct holdings to begin with, instead investing the bulk of their portfolios in commingled funds. Georgetown only agreed to divest from coal, despite those investments making up a minute portion of the school’s $1.5 billion endowment. Stanford gets the most fanfare for their 2014 announcement pledging to divest from coal. Yet a mere two years later, the school voted to reject full divestment. Harvard has repeatedly rejected student attempts to force divestment, and Princeton continually resists the small movement on campus. Activists like to point to the University of California as an example of divestment, but officials made clear the decision to sell the fund’s coal and oil sands investments was “absolutely” made “for economic reasons” and not social ones.

Claim: Johns Hopkins should divest.

Fact: Johns Hopkins held a divestment forum back in April to explore the issue where several panelists spoke to how the act is ineffective and costly.

Frank Wolak, head of Stanford’s energy and sustainable development program, spoke at the event regarding the limited financial impact of divestment on targeted companies, saying, “Even if all universities decided to divest, this would have no effect on global equity markets and no effect on the ability of these companies to raise capital.”

Rafael Castilla, who is in charge of investments at the University of Michigan’s Investment Office, mentioned the hypocrisy of “demonizing” fossil fuels, while at the same time using them for a vast majority of our energy generation.

The Johns Hopkins administration has also been leery about committing to divestment. University President Ronald J. Daniels recently told the school newspaper:

“It’s important to figure out how to draw principled lines around what you would want to divest if you decide to divest. If you are going to think about divestment, is it just coal? Is it all fossil?’ …One could go on and on in terms of things that we find odious about types of corporate behavior. But then the question is ‘are every one of these going to be a target?’ That was an important theme that came up in the session last night.”

Bottom Line: Clearly divestment is not in the best interests of JHU. While it’s laudable that students are trying to better their communities and the climate, unfortunately divestment isn’t the solution they’re hoping for.

Kenyon College trustees just announced that the school will not divest its endowment of fossil fuels, instead putting priority on endowment returns. According to the Kenyon Collegian, trustees said divestment would not have an impact on the environment and they did not see divestment as a way to effect change.

The decision comes after a lengthy campaign by the campus group DivestKenyon. Trustees addressed the issue following an April 20 meeting between the divest group and a representative from the college’s board of trustees. DivestKenyon had been calling for the board to divest its $208.9 million endowment from all fossil fuel holdings—reportedly totaling seven percent of the overall endowment.

Most recently, DivestKenyon demonstrated in front of an inn on the college’s campus which prompted the Kenyon Board of Trustees to directly respond. Joseph Lipscomb, chair of the Budget, Finance and Audit Trustee Committee said, “Divestment is not going to change things – it’s just not.” Lipscomb went on to say that the board acknowledges climate change as a real threat, but does not believe divestment will produce any impact on the environment. In addition, the trustee committee does not “want to make investment choices that could lower endowment returns, thereby preventing people from attending Kenyon.”

Lipscomb’s concerns are valid as a recent study conducted by University of Chicago Professor Daniel Fischel shows divesting a school’s portfolio can eliminate 23 percent of returns over a 50-year timeframe. Endowments are vital to maintaining a college’s overall financial stability and factor heavily into budgets. Less money in the budget means less money the school can spend on things like tuition assistance, scholarships, and student programming.

Kenyon’s decision follows many other notable colleges and universities in rejecting divestment, including Harvard and most recently, Washington University.

UPDATE (4/28/17, 10:00 am EST): Turns out we were right.

Environmentalists seemed to run with the news that Harvard was “pausing” investments in fossil fuels. Bill McKibben said Harvard had “de facto divested from fossil fuels” calling it a “huge win.” His group 350.org went as far as to issue a press release about the announcement.

But in the end, nothing has changed and Harvard has not divested.

In a statement, Harvard Management Company spokesperson Emily Guadagnoli said Colin Butterfield’s comments were “referring solely to his analysis of investments within the natural resources portfolio and how they contribute to the financial strength of the endowment… It certainly was not a change in Harvard’s stance on divestment from fossil fuels, which was laid out in 2013 and remains the university’s position. ” (emphasis added)

— Original Post, April 27, 2017 —

The Harvard Crimson released an article based on comments from Harvard Management Company’s head of natural resources Colin Butterfield, noting that the university was “pausing” investments in some fossil fuels. Naturally, 350.org’s Bill McKibben took to twitter to turn the article into something that it’s not, stating “they won’t call it ‘divestment’ but Harvard ‘pausing’ fossil investments.” Once again, 350 failed to acknowledge what the comments from Harvard actually mean.

Here’s what you need to know:

In 2013, Harvard explicitly rejected divestment and has not changed its stance since. Addressing the university community, President Drew Faust stated, “we maintain a strong presumption against divesting investment assets for reasons unrelated to the endowment’s financial strength and its ability to advance our academic goals.”

Faust also stated in September 2015, “I don’t think that divestment is an appropriate tool, because I don’t think the endowment should be used for exerting political pressure. It is meant to fund the wide range of activities that the University undertakes. As we said before, 35 percent of our operating budget comes from the endowment. That is why people gave their funds to create the endowment. It should not be used as a weapon to exert pressure on one group or another. There are many dangers and it has little effective outcome. What would it mean if we sold our investments? Very little, because there are plenty of other people who will invest in those firms.” These positions have not changed. Period.

In fact, just last month, the university responded to pressure to divest from coal, stating “We agree that climate change is one of the world’s most urgent and serious issues, but we respectfully disagree with Divest Harvard on the means by which a university should confront it.”

According to Butterfield, “I doubt that we would ever make a direct investment with fossil fuels. But that’s more of an Investment Committee decision, and I cannot talk on their behalf.”

For starters, Butterfield is correct that those decisions lay with the Investment Committee and are not within his power to make. Secondly, the Harvard Management Company manages “money both on internal trading and direct investment platforms, as well as through investment arrangements with third-party managers.” Even if the university does hold off on additional direct investments in fossil fuels, it still holds these funds via indirect investments.

That’s a good thing for the endowment’s ability to diversify and invest in a sector critical to the economy. According to a report from Prof. Fischel, “the energy sector has the lowest correlation with all other sectors, and therefore the largest potential diversification benefits relative to the other nine sectors.” In turn, there are “substantial diversification costs associated with fossil fuel divestment.”

Harvard’s endowment, like many others, did struggle over the last year, and as described above the energy sector’s decline is a factor to consider. As Harvard’s 2016 endowment report notes, “S&P 500 earnings declined by 4.0% during the fiscal year, largely attributable to reduced earnings in the energy sector as commodity prices dropped to multi-decade lows.” These lows are a part of any cyclical commodity, and — after finishing in last place for two years in a row — S&P Energy was the best performing index in 2016, rising more than 25 percent. The point is that stocks go up and down, but large institutions like Harvard make investments for the long term, not based on market fluctuations.

While it may be easy to assume Butterfield’s comments are simply focused on the energy sector, the reality is Harvard’s natural resource investments go far beyond energy. Just look at Butterfield’s background, described as a “farmland investor.” These investments weigh heavy towards things like timber and vineyards. As described in Harvard’s September 2016 endowment update:

“The macro environment for direct natural resources investments was challenging as commodity prices continued to decline for much of the fiscal year. Market transactions for timber and agricultural land in many regions were limited, impacting portfolio liquidity in the short term. The portfolio trailed its benchmark by over 1100 bps, primarily driven by unfavorable market and business conditions across two assets in South America.

“One asset experienced severe drought during the crop season as well as an unusually high cost of production. The valuation of the second asset declined as a result of a challenging economic and political environment that made it increasingly difficult to secure financing. As I detail in the Organizational Update, we have hired a new head of our natural resources portfolio and are optimistic we can improve performance in this asset class going forward.”

In fact, Harvard’s investments in these timber resources in South America have come under fire on campus, including calls to “stop Harvard’s Argentine mismanagement and exploitation.”

Butterfield expresses concerns with the impact of natural resource development – and given his background in timber and agriculture he likely has seen how companies can have an impact on their environment. But the idea that giving up investments does anything to alter these companies or their practices – regardless of their industry – is false. As Prof. Fischel of the University of Chicago Law School states, “Every bit of economic and quantitative evidence available to us today shows that the only entities punished under a fossil-fuel divestment regime are the schools actually doing the divesting—with virtually no discernible impact on the targeted companies.”

Robert Stavins, the director of Harvard’s environmental economics program, also stated in June 2015 “The concerns of the students are understandable but the message from the divestment movement is fundamentally misguided. We should be focusing on actions that will make a real difference.”

According a report Led by Dr. Bradford Cornell, a visiting professor of financial economics at Caltech and a senior consultant at Compass Lexecon, Harvard would experience a $107 million per year financial loss if the school chose to divest from fossil fuels. And that cost is regardless of the performance of fossil fuels.

A report from Prof. Hendrik Bessembinder, professor of finance at the Arizona State University’s Carey School of Business, finds the transaction and management costs related to divestment have the potential to rob endowments of as much as 12 percent of their total value over a 20-year time frame. This includes the immediate transactions costs, as well as ongoing management fees to stay in line with the changing definition of “fossil free.” Prof. Bessembinder estimates these frictional costs could cost a typical large endowment fund growing at a historically reasonable rate between $1.4 and $7.4 billion in value over a 20-year period.

Bottom Line: It is no wonder Harvard continues to say no to divestment. Worth over $30 billion, the university’s endowment serves as the school’s largest financial resource, “a perpetual source of support for the University and its mission of teaching and research” and a “financial foundation for the University for generations to come.” Harvard’s endowment ranks first in the nation among universities.

No symbolic action is worth risking this value.

Divest Harvard has tried (and failed) several times to compel their University to sell off its fossil fuel investments. Last week the student group was at work again, blocking the entrances to an administration office building in Harvard Yard.

The purpose of this demonstration was to secure a meeting with university officials and to push Harvard’s endowment to no longer invest in coal and other “dirty energy” industries – despite the fact that the group itself admits Harvard currently has little to no investment in coal. After meeting with students late last year, two members of the Harvard Corporation confirmed “Harvard does not invest in the coal industry at this time,” but would not commit to divesting from coal in the future.

The recent events prompted the Harvard Crimson, the historic student newspaper, to weigh in on the issue. In a scathing editorial, the paper criticized protesters and the merits of divestment. As they note, this is just the latest of several rebuffs to divestment the paper has issued:

“We have expressed our criticism for the strategy of divestment many times in the past. Though the specific demands of Divest Harvard have changed, their underlying philosophy toward combating climate change has not. Simply put, it is the supply of and demand for fossil fuels that creates the market valuations of energy companies, not the reverse. Divestment has no ability to alter these basic economic realities.”

Because divestment has no financial impact on targeted companies, the action of selling Harvard’s investments in fossil fuels—estimated at only 0.2 percent of the overall endowment—can only be seen as a symbolic and empty gesture. That is because once these shares go on the market other investors will simply acquire the holdings. From the Editorial:

“In the unlikely event that Harvard’s sale were to temporarily depress the valuation of these companies, the amount of gasoline pumped, electricity used, and heating oil needed would still remain unchanged. So too would the amount of oil drilled, coal mined, and natural gas harvested. Harvard might be the poorer, but emissions would be the same. Any case for divestment therefore operates purely on the symbolic level. Given that Divest Harvard’s most recent protest merely argued for the formalization of the coal investment moratorium Harvard has already instituted, they have conceded as much.”

The Crimson’s Editorial Board also underlined the risky nature of divestment. Despite having no tangible upside for the University, divestment could have a detrimental impact on students and the University itself. From the piece:

“In more normal times, it might be tempting to see divestment, however ineffective on various levels, as a no-risk option. Suffice it to say that these are not normal times. As Harvard has long argued, using the endowment as a political tool is risky… Such measures would be deeply harmful to the endowment’s ability to finance Harvard’s mission.”

Risky is right. Thanks to research conducted by Prof. Cornell we know just how much divestment would cost Harvard in the long run. If Harvard sold off its fossil fuel holdings it would amount to loses of nearly $108 million annually translating into a near 16 percent shortfall over 50 years. Those numbers would no doubt impact Harvard’s ability to dole out scholarships, fund research or expand its faculty.

Harvard also isn’t the only school in the region resisting divestment. As Divestment Facts has pointed out before, Massachusetts has racked up a pretty dismal record for divestment activists. Most of the state’s most prominent schools have rejected divestment, including MIT, Tufts, Boston College and Northeastern.

Harvard has consistently seen divestment for what it is: all cost and no reward. The Crimson has followed suit, encouraging those concerned about the environment to seek practical solutions versus, as they put it, “the impulse to feel good about our high-minded moralism.”

As the New Year rolls in, the team at DivestmentFacts.com has taken a look back at the semester and what it meant for the divestment movement. From new rejections to examples of student and faculty support against the issue, here is what the past few months have meant for this campaign.

Notre Dame

This September, Notre Dame President Fr. John Jenkins announced the implementation of a five-year sustainability plan while rejecting divestment. From his remarks:

“Nearly all acknowledge that there is no practical plan by which we could cease using fossil fuels in the immediate future and continue the work of the University. It seems to me at least a practical inconsistency to attempt to stigmatize an industry, as proponents of divestment hope, from which, we admit, we must purchase.”

The Notre Dame rejection comes as a huge blow to the divestment movement, which has led a concerted effort to lobby Catholic institutions to divest following the Pope’s call to action on climate change. But as we’ve noted, Notre Dame follows a number of other Catholic universities including Boston College, which have also said no to divestment on the basis of its ineffectiveness at supporting the environment, not to mention its high costs.

Univ. of Pennsylvania (UPenn)

This year, UPenn also joined the Ivy League ranks of Harvard, Brown and Cornell in rejecting divestment by a unanimous decision earlier this fall. The UPenn Board ultimately concluded that fossil fuel use simply cannot be placed on the same moral plane as other social issues the university has taken a stance on, such as genocide and apartheid. In an official letter to Fossil Free Penn, Chairman David Cohen explained:

“The Committee unanimously found that the Fossil Free Penn proposal does not meet the established criteria for divestment. As a result, the Committee did not recommend divestment… While the Trustees recognize that the ‘bar’ of moral evil presents a rigorously high barrier of consideration, we are resolute in our belief that such a high barrier must be maintained so that investment decisions and the endowment are not used for the purpose of making public policy statements.”

In fact, unlike some of the “moral evils” activists try to compare to fossil fuels, our society and economy heavily depends on reliable, affordable energy access. As featured in the World Energy Outlook, “access to modern energy is essential for the provision of clean water, sanitation and healthcare and for the provision of reliable and efficient lighting, heating, cooking, mechanical power, transport and telecommunications services.” The Energy Information Administration (EIA) has also stated multiple times that oil and gas will constitute 80 percent of the world’s energy use by 2040 while overall energy consumption worldwide will continue to grow by 56 percent during that period.

Rice University

Some schools went a step further than just pointing out the hypocrisy and impracticality of fossil fuel divestment by highlighting how successful investments in the energy industry have allowed endowments to thrive. Rice University, which has deep historical roots in the energy industry, has traditionally relied on oil and gas assets as a “productive source[s] of revenue” to the Rice Endowment.

More recently, Allison Thacker, President and CIO of the Rice Management Company echoed this sentiment regarding energy investment’s role in increasing the value of the endowment, stating:

“I do not consider blanket divestment to be the solution for sustainability in the future… We have a policy stating that Rice does not endorse nor boycott products. We have successfully invested in fossil fuels and natural resources and have collaborated with the energy industry in other ways as well.”

Blanket divestment has been criticized by other academics like Frank Wolak, director of the Program on Energy and Sustainable Development at Stanford, who argued that divestment “comes at the expense of meaningful action” as it does nothing to reduce global greenhouse emissions.

Harvard Court Case

Despite Harvard University’s long opposition to divestment, a small group of student activists recently turned to litigation tactics to try and revive the failing campaign’s momentum on campus. In 2014, the Harvard Climate Justice Coalition filed a lawsuit claiming investment in fossil fuel companies is “a breach of fiduciary and charitable duties as a public charity and nonprofit corporation,” asking the court to demand Harvard “immediately withdraw” its holdings. To activists’ dismay, the Massachusetts Appeals Court ruled against the students in a unanimous decision this fall – determining Harvard University is not legally required to divest.

What’s more, the Appeals Court agreed that students’ claims of “fossil fuel investments have a chilling effect on academic freedom and have other negative impacts on their education at the university…were too speculative, too conclusory, and not sufficiently personal to establish standing.’’ With their means to legal recourse effectively shut down, it’s safe to say the divestment conversation at Harvard is over.

Northeastern University

While the Harvard court case defeat of divestment drew a good deal of media attention, Northeastern University quietly rejected divestment in July, opting instead for investing in sustainability efforts. In the underreported announcement, Treasurer Thomas Nedell stated:

“We have deliberately chosen to invest, not divest. This approach is consistent with Northeastern’s character as an institution that actively engages with the world, not one that retreats from global challenges.”

Northeastern Professor Matthew Nisbet also wrote that divestment leader Bill McKibben’s efforts, “make for potent cultural symbols, but such strategies can deflect attention from far more substantive goals.” The Northeastern rejection is a clear call for open engagement with the energy industry over symbolic divestment.

University of Denver

The University of Denver sought to take a deeper look at divestment this year through a series of hearings held by the DU divestment special task force. The 350.org-run campaign in Denver met staunch resistance from faculty members and local financial specialists during the hearings. Wendy Dominguez of the Denver-based Innovest Portfolio Solutions discussed the hidden costs of fossil fuel divestment, warning that increased portfolio risk and underperformance could threaten the viability of endowment-funded academic programs. From her remarks:

“You can’t just set the policy and expect the managers to go ahead and do this. We think you have to continually circle back [to check] that there aren’t securities getting into their portfolio that are in conflict with the policies. That is an additional fee for a consultant like us.”

Another report by Arizona State University finance Professor Henrik Bessembinder similarly found that the transaction and management costs related to divestment have the potential to rob a medium-sized endowment fund like DU’s of $52 million to $298 million over a 20-year time frame. Echoing the opposition voiced by various academics and faculty to DU’s divestment, Divestment Facts recently held an energy forum in Colorado in which economists, industry leaders and the University of Colorado Regent-elect Heidi Ganahl urged DU to reject the proposal to divest. As Ganahl noted,

“Universities across the country, including the University of Colorado, have determined that it is in the best interests of their missions, their students and other constituents to have a diversified investment portfolio, which includes the energy sector. They have rejected calls for divestment not only because it is a questionable investment strategy, but also because the direct beneficiaries of investments are students who receive scholarship funds and faculty whose research is supported in part by investment income.”

On the same day that Colorado leaders came out against university divestment, Divestment Facts also launched a social media campaign to raise awareness of fossil fuel divestment and how abandoning oil and gas investments could reduce important financial aid and scholarships. The animated video explains,

“When a school sells of shares of a fossil fuel company, they don’t just disappear. Someone else buys the stock. There is no financial harm to companies, nor any gain for the environment.

And people are listening. In an editorial, The Denver Post, called DU divestment “unrealistic and unwise” given the important role fossil-fuel development plays in Colorado and the nation. The board further highlights divestment’s cost to the endowment and inability to have an impact on the environment, writing,

“[T]aking 350.org’s marching orders would harm DU’s ability to serve its students, and constrain its ability to invest in companies ‘that are also working on meaningful change’…Further, it’s also not even clear that such a divestment would have any impact whatsoever on climate change.”

The debate in Denver will certainly be one to keep an eye out for in 2017 as the social media campaign continues to roll out and shape the divestment conversation in Colorado.

Barnard College

This December, the Barnard Task Force on Divestment officially recommended that the Board of Trustees vote to divest from coal and oil sands companies and those that “actively deny climate change.” While a small step forward for divestment advocates on campus, it’s worth highlighting that the Task Force recommended only a symbolic divestment gesture, while categorically rejecting full divestment of fossil fuels, calling the act “too broad” and saying it “lacks…science-based differentiation.” From the report:

“…A blanket ban on an entire industry would raise questions of academic and scientific bias; Barnard-based research relating to fossil fuels could be questioned because it is supported by an institution that has taken a stand against the sector as a whole.”

In the report, Barnard also noted that “most institutions of higher education that have considered the divestment question have chosen not to divest” and that its own divestment efforts would be “on-going exercise, requiring constant review and probably additional management expense.” The Board of Trustees is set to make a final decision on divestment in March 2017.

Boston University

Boston University’s Board of Trustees also moved forward with a limited divestment decision this fall, including “efforts to avoid investments in companies that extract” coal and oil sands. A clear example of the Syracuse model – divesting only from direct investments, or investments one doesn’t even have – BU Today highlights that the decision isn’t even a real divestment as the school is not selling anything. From the report:

“The trustees noted that total avoidance of coal and tar sands companies may not be possible, because the University’s portfolio includes vehicles such as mutual funds, whose managers choose stocks, and passive index investing. That latter is tied to the performance of a particular stock index—say, the S&P 500—whose holdings BU has no say over.”

BU’s $1.6 billion endowment is largely invested in limited partnerships and commingled funds, making an actual divestment effort extremely difficult to perform. Even Divest BU agreed, stating “BU remains invested in the fossil fuel industry” and that the university used “vague language that does not guarantee a commitment to divestment.”

Deflated and Debunked, Divestment limps on into the New Year

This year, the divestment campaign met resistance, rejection and a heavy dose of reality at every turn. Despite an Arabella Advisors report falsely claiming $5.2 trillion in divestment pledges have been made across the globe, Divestment Facts quickly debunked the over-exaggerated number. It turns out that—similar to Arabella’s $2.6 trillion claim from 2015—the report is an aggregation of the total value of combined assets of institutions that it claims have “pledged to divest.” Mother Jones noted, “that big number — $2.6 trillion—has nothing to do with the amount of money that is actually being pulled out of fossil fuel stocks” and further called out Arabella for having “no idea how much money the institutions surveyed have invested in fossil fuels, and thus how much they pledged to divest.” Even one of the media’s biggest proponents of divestment, The Guardian, admitted “it is often difficult to calculate the precise proportion of fossil fuel investments in complex funds, but about $400bn of the $5.2tn total is likely to be in coal, oil and gas.”

While the report leaves plenty of questions left to be answered about the real facts and figures behind the divestment movement, one thing goes without saying: fossil fuel divestment has real costs, little to no impact on the environment and no place on college campuses in the New Year.

At the University of Denver (DU) Divestment Task Force hearing this Thursday – the sixth in a series – the task force will be hearing from DU professors, including the president of the DU Faculty Senate that passed a resolution endorsing divestment and the chair of the Faculty Senate Divestment Committee who signed an open letter supporting divestment. But lest one assume that the DU faculty unanimously supports divestment, here are a few things you should know before the hearing.

Sharp Divisions Within Faculty Senate on Divestment

Wrapping up his two-year term as head of the Faculty Senate, then-president Dr. Arthur Jones summarized the council’s proceedings on divestment in the annual president’s report in June 2016. According to Dr. Jones’ account, there was “considerable disagreement” within the Senate’s ad hoc committee on divestment over the resolution recommending a “symbolic recommendation for divestment on moral grounds.” In fact, even though the majority of the committee members voted to move forward with the resolution, they also emphasized that there was insufficient information about the university’s endowment and the potential impact of divestment on financial aid:

“While there was considerable disagreement on the committee, a majority of members voted to move forward with a resolution for the Faculty Senate that would include a symbolic recommendation for divestment on moral grounds, emphasizing the fact that there was insufficient information about the university’s endowment to justify a more substantial recommendation on the issue. (Several committee members were particularly concerned about the fact that there is not enough information available currently to determine whether a decision to divest would impact negatively the institution’s efforts to increase resources for financial aid).”

Although the committee members disagreed about divestment, they voted unanimously to put the focus on other, less contentious ways for the school to respond to climate change:

“Despite disagreement on divestment, the committee voted unanimously to have the resolution put a primary emphasis on recommending other, publicly visible steps that DU can take to contribute to a national effort to combat climate change.”

Shortly after, the DU’s Board of Trustees announced the decision to launch a task force – the task force that has been holding a series of hearings on divestment – to conduct a “comprehensive, publicly visible exploration of all sides of the divestment issue.”

Faculty Senate President Questioned “Wisdom” of Voting on Divestment Ahead of Task Force Proceedings

Because the task force’s hearings would be held throughout the fall of 2016 and the Board of Trustees would not be making a final decision until January 2017, Dr. Jones questioned the wisdom of having the full Faculty Senate vote on the divestment committee’s resolution in May, before the Board of Trustee’s task force proceedings even began:

“I had authorized placing the resolution on the agenda for the final meeting, primarily to bring closure to this piece of Faculty Senate business before passing the presidential gavel to my successor, Kate Willink. However, I remained ambivalent about the wisdom of moving forward with the resolution given the opportunity to study the issue further and to contribute in a more informed way to the Board’s upcoming, organized public exploration in the fall.”

Because of this ambivalence, Dr. Jones welcomed a motion to delay a vote on the resolution. The motion, however, was defeated by a 68 percent majority, despite 14 faculty members voting in favor of a delay.

Therefore, without having had the opportunity to review the information to be presented during the task force’s hearings or to consider the outcomes of its deliberations, the Faculty Senate went ahead with a vote on the divestment committee’s resolution and approved it with a 70 percent majority, with 12 members voting against divestment. Put another way, if the vote is representative of DU’s faculty, then almost a third of the faculty would be opposed to divestment.

Recommendations to Put Divestment Aside and Focus on Less Contentious Issues

Just as the Faculty Senate’s divestment committee voted unanimously to put a “primary emphasis on recommending other, publicly visible steps that DU can take” in response to climate change, Dr. Jones recommended that the Board focus on other points outlined in the resolution, “beyond divestment,” that received more support from members of the senate:

“Hopefully the Board will focus particular attention on the portions of the resolution, beyond divestment, that garnered nearly unanimous support in both the first and second Faculty Senate readings and discussions.”

These suggestions include allocating funds to efforts designed to achieve carbon neutrality, reinvesting in renewable energy technologies and integrating sustainability into the curriculum.

Even Resolution Backing Divestment Acknowledged Its “Symbolic,” “Incomplete” Nature

The resolution that the Faculty Senate passed in favor of divestment recognized that any move by the university to divest would be “symbolic” and an “incomplete response to the climate crisis”:

“Because neither our committee nor the Faculty Senate control University endowments, we realize our recommendation is symbolic. …

“Should the University decide to divest, divestment alone would be an incomplete response to the climate crisis.”

Incidentally, the symbolic nature of divestment is the very reason why many prominent universities have refused to divest. When Pomona College President Dr. David Oxtoby announced the Board of Trustees’ decision not to divest, he explained that even the symbolic action of divestment would nevertheless carry a “significant cost”:

“It also remains unclear that divestment would have anything more than a symbolic impact in fighting climate change. …. Although symbolism does matter, it is hard to make the case that it would be worth the significant cost to future Pomona students.”

Other universities highlighted the inconsistency between the symbolic act of divestment and the need to continue relying on fossil fuels. Davidson University President Carol Quillen wrote,

“…[W]e question the integrity of making a symbolic gesture while continuing to power our campus with energy produced from fossil fuels.”

Just last week, Notre Dame University rejected divestment, and president Fr. John Jenkins explained the decision this way:

“Nearly all acknowledge that there is no practical plan by which we could cease using fossil fuels in the immediate future and continue the work of the University. It seems to me at least a practical inconsistency to attempt to stigmatize an industry, as proponents of divestment hope, from which, we admit, we must purchase.”

Making symbolic statements through divestment would also run counter to the mission to educate, wrote Brown University President Christina Paxson:

“As I and others considered the matter, it became apparent that the symbolic statement of divestiture would not elucidate the complex scientific and policy issues surrounding coal and climate change and, for this reason, it would run counter to Brown’s mission of communicating knowledge.”

Similarly, in a column supporting Harvard University President Faust’s decision not to divest, Director of the Harvard Environmental Economics Program Robert Stavins wrote,

“One major problem is that symbolic actions often substitute for truly effective actions by allowing us to fool ourselves into thinking we are doing something meaningful about a problem when we are not.”

DU’s own Dr. Frank Laird, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, expressed a similar sentiment when he addressed the task force a few weeks ago:

“[Divestment] is not really ineffective, but I think it can have a negative effect on de-carbonizing the energy systems because, frankly, it’s a distraction from the large and complex task we need to face.”

Given the sharp divisions within the Faculty Senate on divestment, the misgivings of the former Senate President regarding the divestment resolution and the resolution’s own recognition that divestment would be “symbolic,” one question looms large ahead of DU’s hearing on Thursday: Will the task force hear from faculty members who oppose divestment?

This Thursday, as the University of Denver (DU) Divestment Task Force holds its sixth hearing on fossil fuel divestment, we have to believe the presentation from divestment supporters will go far better than it did last time.

In the process of trying to explain the merits of fossil fuel divestment to the task force at the last hearing two weeks ago, a divestment activist demolished her own campaign’s rationale and talking points in real time. Without even realizing it, “Political Liaison and Narrative Strategy Consultant for Divestment Student Network” and 350 Action organizer Michaela Mujica-Steiner demonstrated just how political and pointless the divestment campaign really is, and how, at the end of the day, it amounts to nothing more than symbolic nonsense.

Are Fossil Fuel Investments Risky? 350.org Says Yes and No.

From the very beginning, 350.org has argued that its divestment campaign is a moral initiative that also makes financial sense. Fossil fuel companies are “very risky investments,” 350.org has explained, as “energy markets [are] particularly volatile, and therefore risky.” One of the slides in Mujica-Steiner’s presentation is titled, “The Fossil Fuel Industry is a Risky Business.” Because of this riskiness, “[d]ivestment can make good financial sense for your portfolio,” and “[d]ivestment now could protect your assets in the future,” argues Green America, a group that works with 350.org on divestment.

But when given the opportunity to explain how the fossil fuel industry was riskier and more cyclical than other industries – and therefore warranted divestment while other sectors did not – Mujica-Steiner just couldn’t. In fact, she said the fossil fuel industry was just like other sectors, and perhaps the entire economy: In her words, the fossil fuel industry “might be,” and “probably is,” marked by the “same cycle” when compared to other resources and other markets, and “maybe it’s almost the nature of our economy to be a boom and bust cycle”:

“It may not be that different from some other industries and I’ll admit I don’t know as much about other industries so I can’t really speak as much to how other industries function in cycles. … So it might be the same cycle in terms of other resources. I would imagine and speculate that it probably is. And maybe it’s almost the nature of our economy to be a boom and bust cycle. I’m not, I’m not sure because it seems like that would probably happen in other markets as well, but I would say that especially when you’re considering, you’re taking renewables into consideration and taking these other factors with the market and the policy regulations, you may see maybe the boom and bust cycle more … highlighted.”

There goes 350.org’s financial rationale for divestment. But this kind of fumbling financial illiteracy is only to be expected, given that 350.org activists have admitted on their Frequently Asked Questions page that they didn’t really know much about the subject matter, aside from “a few tips” from financial experts:

“Divestment sounds complicated. Do I have to be an expert to start a divestment campaign? Nope — none of us at 350.org are experts on financial markets, but we’ve talked to a lot of divestment experts and they’ve given us a few tips.”

Financial Experts, Analysts, Universities Reject Divestment

Well, actual financial experts have spoken out against the divestment campaign, arguing that divestment would contradict a school’s fiduciary responsibility to maximize the value of its portfolio in order to advance its academic mission. At the DU Divestment Task Force’s third hearing, Wendy Dominguez of Denver-based investment consultancy Innovest Porfolio Solutions explained that divestment would entail increased portfolio risk, underperformance, and a threat to endowment-funded educational programs. At the task force’s fourth hearing, Kristy LeGrande and Wendy Walker of investment advisory firm Cambridge Associates laid out the challenges of divestment from an investment perspective, including how investment strategies for most endowments involve commingled funds, that screened funds are not typically offered by the most high quality investment managers, and that the track record for the “handful” of hedge fund strategies that are explicitly “fossil fuel free” is very limited.

Economic studies commissioned by Divestment Facts, as well as internal evaluations by universities like Swarthmore College and Wellesley College, have drawn the same conclusion: Fossil fuel divestment would be extraordinarily costly. For example, a study by University of Chicago Prof. Daniel Fischel found that divestment would cost university endowments almost $3.2 billion every year. In addition, another study by Prof. Hendrik Bessembinder of Arizona State University’s Carey School of Business concluded that the transaction and management costs related to divestment could potentially rob endowment funds of as much as 12 percent of their total value over a 20-year timeframe.

It is precisely because divestment would be detrimental to a school’s education mission that universities have overwhelmingly rejected divestment, outnumbering those that have pledged full divestment by a ratio of 111:1. It’s why schools like Harvard University, 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben’s alma mater, and Middlebury College, where McKibben is a scholar in residence, have both refused to divest. Even the three schools that top Sierra Club’s list of America’s Greenest Colleges – schools that are “dedicated to greening every level of their operation” – have rejected divestment: University of California, Irvine, American University and Dickinson College.

350.org: Divestment Is About “Changing the Story” Rather Than “Material Changes”

Given the divestment campaign’s string of failures, what, if any, are its contributions? “Changing the story,” Mujica-Steiner told the DU task force, “rather than … material changes,” in order to “restrict the social license of the fossil fuel industry” and “to stigmatize the fossil fuel industry”:

“From my perspective, fossil fuel divestment, while there’s been a large amount of commitment and even that moving, the moving of investments, and divestment, really I would say the purpose is to restrict the social license of the fossil fuel industry, meaning to stigmatize the fossil fuel industry as more a part of social change rather than these material changes. And that’s actually why I didn’t, in terms of what I think are really putting fossil fuel investments at risk, I didn’t really highlight the fossil fuel divestment movement, because I don’t think it…has been detrimental to the market or detrimental to impacting demand. I think what it’s been really successful in doing has been changing the story, so around the fossil fuel industry, and brought to light…and kind of brought some of these issues more into the public policy arena. … In general its focus has been more social than materially impacting demands.”

350.org’s “changing the story” might as well mean distracting universities from pursuing solutions to energy problems in all their complexity, as DU Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Dr. Frank Laird has said:

“[Divestment] is not really ineffective, but I think it can have a negative effect on de-carbonizing the energy systems because, frankly, it’s a distraction from the large and complex task we need to face.”

To recap, 350.org activists have replaced students in what was purportedly a student-led college campaign, attempted to deprive universities of billions of dollars used for financial aid, faculty salaries and academic programs, distracted schools from advancing their education mission, and completely failed to provide a coherent case for their own campaign. What, then, is left for these activists? The moral high ground, according to 350.org operate Brett Fleishman, who has also testified before the DU task force: “[T]his is a moral campaign at its core.” But, in the words of University of Colorado Denver instructor Lisa Hamil, “is it moral or ethical to sacrifice the quality of a student’s education just to make a political statement?” The answer is an obvious no.

Colorado energy workers showed up in numbers today at the University of Denver with a simple message: Don’t endorse the anti-fossil fuel agenda of 350.org.

DU is currently considering a proposal to divest the university’s endowment from investments tied to oil, natural gas or coal. A special DU task force, formed in July, has received testimony from university officials, investment advisors and from 350.org, the group behind the national college divestment campaign. Today, at the fourth hearing of the task force, DU officials took public comment from the fossil fuel industry for the first time.

Twenty-five energy workers and industry supporters – compared to just one divestment activist – attended the task force meeting to hear a presentation from Simon Lomax, Denver-based adviser to Divestment Facts. His presentation was a direct response to Brett Fleishman, a 350.org official based in California, who testified before the task force in early August. At that hearing on Aug. 4, only two divestment activists attended to show their support.

In an hour-long presentation, Lomax offered a look at the real costs of divestment for universities, the growing list of failures of 350.org’s anti-fossil fuel campaign, and the critical role of the energy sector in Colorado’s economy. He told the task force about the divestment campaign’s singular focus on demonizing energy companies and energy workers and the involvement of 350.org in a series of anti-fracking ballot measures that have been met with broad, bipartisan opposition in Colorado. Lomax also showed the task force that even climate advocates – such as Robert Stavins of Harvard and Roger Pielke Jr. of the University of Colorado – have sharply criticized the divestment campaign and the tactics of 350.org.

Targeting DU was a curious decision for 350.org because the university already has a strong track record on cutting emissions, Lomax said. DU has cut carbon emissions by 15 percent since 2006, even as the university has grown, enrolling six percent more students and employing five percent more staff over the same period.

“You don’t have to explain yourself to 350.org or any other environmental group for that matter,” Lomax said. “You are walking the walk while they talk the talk.”

“We see this a lot,” Lomax added, unveiling new research from Divestment Facts.

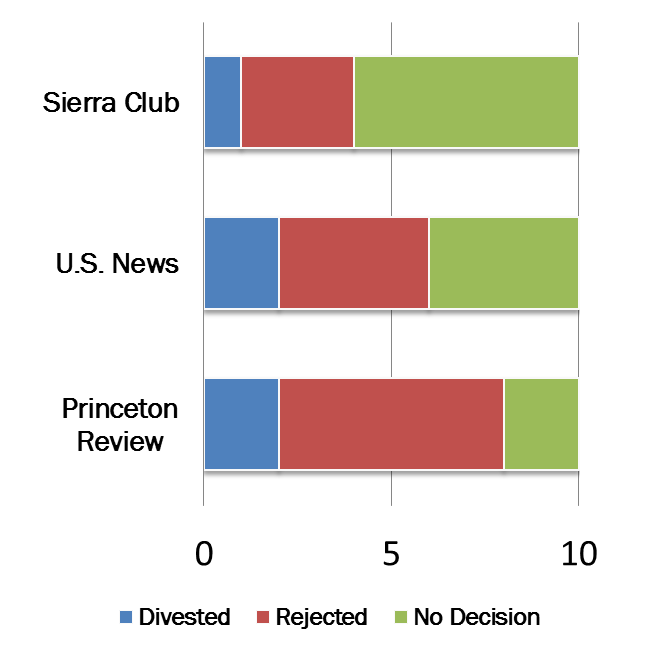

Some of the world’s leading college admissions services like the Princeton Review and U.S. News & World Report publish an annual list of the most eco-friendly schools based on their own metrics. The Sierra Club itself also puts together its list of “Top Green Schools.” What do all three of these lists have in common? More schools on these Top 10 lists have rejected than pledged divestment.

According to the Sierra Club’s list of America’s Greenest Colleges, three of the top ten schools have come out in opposition to divestment while only one school – Green Mountain College — has pledged divestment. Those top three schools, University of California, Irvine, American University, and Dickinson College are all considered “Cool Schools” by the Sierra club and are “dedicated to greening every level of their operation.” Meanwhile, they have each said no to divestment. As University of California Regent Bonnie Reiss stated at UC Irvine in 2015:

“It was really the belief of everyone on this committee, myself included, who cares about climate that simply divesting from a list of a couple hundred companies that the students were presenting would absolutely do nothing. So we sell a few shares and stocks in an oil company. It won’t change their behavior in any way. It’s just symbolism without real impact and maybe gets a quick headline like we saw with Stanford.”

At the Princeton Review, six of their Top 10 Green Colleges have also rejected divestment while only two have pledged divestment. And of U.S. News & World Report’s Top 10 Eco-Friendly Colleges, four of the schools have rejected divestment while only two have pledged divestment.

At the Princeton Review, six of their Top 10 Green Colleges have also rejected divestment while only two have pledged divestment. And of U.S. News & World Report’s Top 10 Eco-Friendly Colleges, four of the schools have rejected divestment while only two have pledged divestment.

It’s clear that divestment and tangible, measurable success in finding climate change solutions do not go hand in hand. As featured in today’s presentation from Divestment Facts, natural gas development, for instance, has actually been a boon for the environment in helping to reduce carbon emissions both in Colorado and the nation. And this development has gone on alongside, and in harmony, with increased renewable development.

Dr. Frank Laird, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at DU, also spoke to this fact in front of the task force earlier this summer, noting how divestment campaigns distract institutions from pursuing solutions and DU’s existing energy research programs. He told the task force,

“[Divestment] is not really ineffective, but I think it can have a negative effect on de-carbonizing the energy systems because, frankly, it’s a distraction from the large and complex task we need to face [emphasis added].”

He continued, citing a study co-authored by Harvard professor Naomi Oreskes, an outspoken divestment advocate, finding that just 18.5 percent of all fossil fuel reserves (oil, natural gas, and coal combined) are privately owned. In turn, he stated since universities cannot invest in them in nationally owned firms to being with “The largest component of the fossil fuel industry is simply irrelevant to what private investors wish to do…So part of the story that we’re going to affect the industry simply misses the largest part of the industry.”

In another presentation at today’s hearing, Kristy LeGrande and Wendy Walker from investment advisory firm Cambridge Associates spoke about the challenges of divestment from an investment perspective. They explained that investment strategies for most endowments involve commingled funds, that screened funds are not typically offered by most high quality investment managers, and that the track record for the “handful” of hedge fund strategies that are explicitly “fossil fuel free” is very limited. They also pointed out that while energy stocks may not have performed as well as other sectors in the short term, over longer time periods – which they explained are more relevant to institutions – energy stocks have performed better than a broader basket of securities.

From today’s task force meeting at DU, it’s clear that 350.org’s “divest or fail” proposition for targeted universities is failing. For schools looking to achieve environmental outcomes, there are real steps they can take towards real solutions. But divestment is simply not one of them.

As students head back to campus this fall, a national campaign aimed at forcing endowments to divest from fossil fuels will no-doubt kick up again, with national organizers from groups like 350.org urging students to rally to the cause. But just how has divestment fared over recent years, and how effective has it been? As the New York Times explains, “on college campuses, where the movement began roughly four years ago, divestment drives appear to be meeting some resistance.”

Whether heading back to campus or simply monitoring this debate as it unfolds, here’s what you need to know about divestment.

More schools are rejecting divestment than moving forward

What do Stanford University, New York University, Cambridge University, George Washington University and the University of Utah all have in common? These are just some of the country’s leading universities that have rejected divestment in the last six months alone, as have top tier schools like Swarthmore College, ironically the birthplace of the divestment movement, and Middlebury College, found in the home state of the divestment movement’s founder Bill McKibben.

As the President of Harvard University, another elite school that has 1) rejected divestment and 2) has the largest endowment of any other university, stated in opposition to divestment, “I don’t think that divestment is an appropriate tool, because I don’t think the endowment should be used for exerting political pressure. It is meant to fund the wide range of activities that the University undertakes. As we said before, 35 percent of our operating budget comes from the endowment. That is why people gave their funds to create the endowment. It should not be used as a weapon to exert pressure on one group or another.”

The few schools that have agreed to divest are only giving up virtually non-existent “direct holdings”

When the University System of Maryland Foundation (USMF) announced it would “divest” from fossil fuels, divestment activists cheered victory. But, as DivestmentFacts.com noted earlier, USMF, along with UMass and the DC pension fund, are examples of empty gesture divestment pledges, also known as users of the “Syracuse model.” In this scenario, like so many others, USMF announced it would only sell direct investments from fossil fuels. Think of it like managing your own personal investment account, where you can sell off individual stocks, versus attempting to manage your 401K account, which is invested in a variety of funds meant to provide a consistent return overtime.

According to the school paper, USFM, for instance, “has no direct investments in coal, tar sands or any companies on the Carbon Underground 200 list.” So what exactly is the school divesting?

USFM is not alone, of course. As Bloomberg explains:

Georgetown University said it would purge its $1.5 billion endowment of direct coal holdings, with President John DeGioia saying climate change “requires our most serious attention.” The Washington university later said the amount involved was “insubstantial.”

Oxford University, calling itself “a world leader in the battle against climate change,” said in May it would avoid direct investments in coal and oil-sands companies in its $2.6 billion endowment. The British university, in fact, held none, it said. Syracuse University similarly announced it would divest from fossil fuels only to say it had no direct holdings.

Last May, Stanford’s President John Hennessy, citing his school’s responsibility “as a global citizen to promote sustainability for our planet,” said the university would divest direct stakes in the 100 largest coal-mining companies. Student activists at Stanford Fossil Free called it “a groundbreaking victory.” The commitment amounts to only a “small fraction” of the portion of the $21.4 billion endowment that the university manages itself, according to Lisa Lapin, a Stanford spokeswoman. Lapin declined to say how much the university manages directly.

By selling only direct funds – much to the applause of activists – endowments can say they have “divested” without having to incur the actual costs of doing so. This is because these schools have little to no direct investments to begin with while the majority of their holdings sit in co-mingled funds.

Unlike schools that follow the Syracuse model, schools that actually divest fossil fuel holdings are looking at an expensive and complex process.

Yes, divestment is really costly for schools

When students and faculty across the country return to campus to enjoy the benefits of their endowment, such as financial aid, research grants and cutting edge facilities, they should keep in mind the real cost associated with divestment that would directly threaten these activities. A recent report by Prof. Hendrik Bessembinder from Arizona State University, for instance, looks at the hidden costs that accompany divestment, including the fixed costs related to complicated transactions and actively managing a “fossil-free” endowment. The report found that a typical large endowment like the USMF would translate into a loss in value of as much as $7.4 billion over 20 years. Those numbers alone should be enough to question the merits of divestment.

Another report from Prof. Daniel Fischel of the University of Chicago published a study that explored the impact on investment revenues, finding schools that sell their fossil fuel assets can expect returns 70 base points lower than their peers. Apply that to the $456 billion that comprises total university endowment assets and this deduction would decrease annual growth by nearly $3.2 billion each year.

Fischel’s conclusions were corroborated in a second study by California Institute of Technology Prof. Dr. Bradford Cornell who explored the impact of divestment on a small group of elite schools. Assessing Harvard, Yale, MIT, Columbia and NYU, he found that if each school divested their endowments, they would collectively experience more than $195 million annually in lost returns. Not surprisingly, each of these five schools has chosen to reject divestment, despite sustained campaigns to force their hands.

Faulty divestment figures reveal little divestment support

Despite claims from groups like Arabella Advisors or The Guardian, the total amount of universities and organizations that have actually divested is quite small. Activists often push over-exaggerated numbers alleging $2.6 trillion or even $3.4 trillion has been divested. But outlets like MSNBC, Mother Jones and The New York Times were all quick to debunk these numbers as flawed and misleading. As Mother Jones explains:

“That big number—$2.6 trillion—has nothing to do with the amount of money that is actually being pulled out of fossil fuel stocks. In fact, the investment consultancy behind today’s report has no idea how much money the institutions surveyed have invested in fossil fuels, and thus how much they have pledged to divest. Instead, that number refers to the total size of all the assets held by those institutions—hence the word “representing” in the quote above from the report. And that’s a huge difference.”

And as noted earlier, many U.S. schools included in this list of institutions that follow the “Syracuse Model” don’t hold or divest any assets at all.

Even still, if this logic was used to calculate the total endowment of schools that have fully divested within the United States, the total amount only adds up to roughly $2 billion dollars. This is because a good portion of schools that have pledged to divest are small colleges with less than 1,000 students like Warren Wilson College and Unity College. If $2 billion sounds like a lot, it absolutely pales in comparison to the $456 billion that constitutes total U.S. university endowment assets. Just comparing it to Harvard University’s $36 billion endowment that rejected divestment makes the case clear.

Divestment has no tangible impact on the environment

Most importantly, and perhaps most ironically, divestment does not accomplish the very objective its supporters claim to fight for. Academics and institutions have agreed that divestment does little in the way of actually reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combatting climate change. The American Securities Project found divestment would “not cause any meaningful financial impact to fossil fuel companies, but could hurt the universities and colleges that depend of fossil fuel share dividends.”

Frank Wolak, the director of the Program on Energy and Sustainable Development at Stanford, has also highlighted the environmental costs of divestment. He states, “Divestment comes at the expense of meaningful action. It will do nothing to reduce global greenhouse emissions. It will not prevent these companies from raising capital.”

Outside of colleges, major endowments, pensions and charitable funds are rejecting divestment, opting for engagement

The Guardian’s original “Keep-It-In-The-Ground” campaign focused on pressuring the Gates and Wellcome Trust to divest from fossil fuels. Both foundations ultimately rejected divestment and opted for real solutions instead. Bill Gates was even more succinct, calling divestment a “false solution” and launching a new Breakthrough Energy Coalition aimed at bringing some of the world’s largest private companies together to invest billions into energy research and development.

As scholars and individuals in pursuit of knowledge, students and faculty members should keep in mind the facts when heading back to school: divestment is an empty gesture that is losing steam. Is it really worth the financial risk?